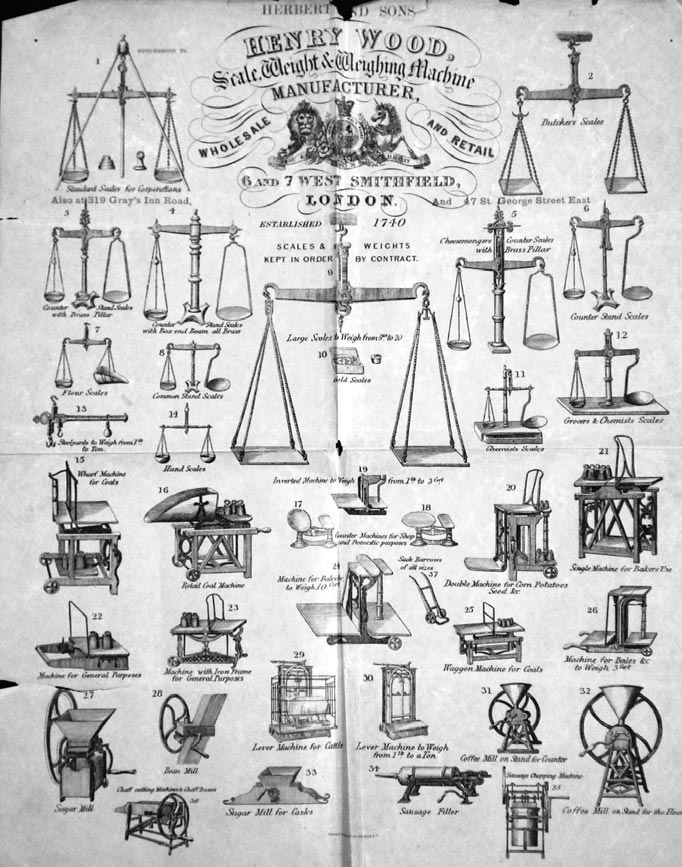

Herbert & Sons was founded by John Wood, and since Victorian times the date has been given as 1760. However recent research shows that the date is more likely to have been around 1740, as shown in the heading of this catalogue from the 1860s. The labels in his scales describe him as ‘Jno Wood at ye Angel & Scales ye corner of Queen Street in Watling Street, London’ who ‘makes and sells all sorts of scales & weights steellards & cocks’. The records show that on the 2nd February 1742 John Wood was admitted as a member of ‘The Cirencester Society’ in London. This organisation had a twofold purpose: the promotion of ‘harmony, good fellowship, and conviviality among Cirencester men living in London’, and secondly the ‘apprenticing of poor Cirencester boys to useful handicraft trades’. 1742 also saw John Wood for the first time entered in the Land Tax Assessment Records at 15 Queen Street, Cheapside, in the City of London. John married Mary, and they had two daughters, the eldest Ann born about 1744 was christened at St Antholin in Watling Street. Unusually for the time, Mary had a business in her own right, that of a bead and necklace maker with premises in Shire Lane near Temple Bar. John was a member of the Blacksmith’s Company, and during his time took many apprentices, including Thomas Goulding (1757) and his nephew Richard (1761), whose father, also Richard, was a leather breeches maker in Cirencester. The Wood business continues ...  John Wood died in March 1765 around the age of 50. After his death his business was taken on by Thomas Goulding, who had been ‘freed’ in 1764. John Wood died in March 1765 around the age of 50. After his death his business was taken on by Thomas Goulding, who had been ‘freed’ in 1764. So how was it possible for Thomas to take over the business in such a short time? Logically his nephew Richard would have taken on the business but he was only 18 years old and had not completed his apprenticeship. Then only six weeks after John’s death in March 1765 Thomas married his former employer’s daughter Ann at St. Antholin a few yards from the premises in Queen Street. Thomas was then aged 23 and Ann 21. Their first child Somerset Goulding was born in 1766, and their second Mary in 1767, but she died the same year. Thomas Goulding ran the business until he died in 1776 at the age of only 34, so Richard then took over. He must have valued the goodwill forged by Thomas as for some years his label stated ‘Richard Wood (late Goulding)’ and to completely forestall any dispute over ownership Richard promptly married Thomas’s widow, who was also his first cousin, John’s daughter. We know a little about Richard Wood from various records. He traded as a scalemaker from 1768 to 1820 – a very long time by anyone's standards. "I am a scale beam maker. On 6th October, Tuesday evening, it may be some little before ten o’clock in the evening, I had just done supper, I thought I heard rather more noise than usual. I opened my door, and found a man of the name of North had a man in possession by the collar, and I was given to understand that he had made his escape out of the next house to mine.” – Richard Wood giving evidence at the Old Bailey, 1795

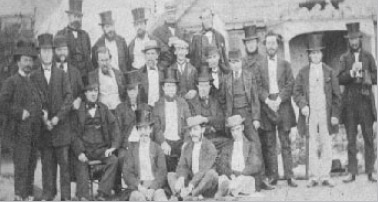

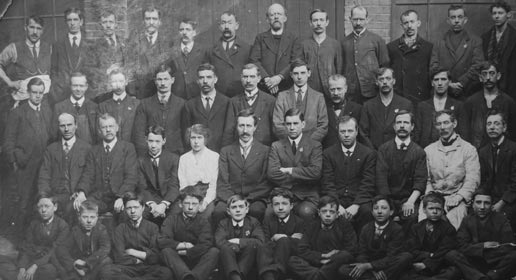

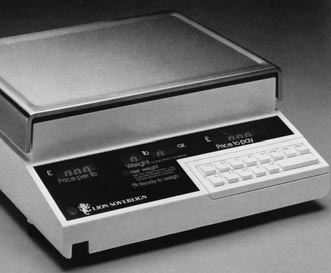

Around 1814 he took over the scalemaking business at 6 West Smithfield of John Wynn, himself a successor to Thomas Croome. Typical weighing equipment of the time is illustrated in many places, but these two woodcuts from ‘London Melodies & Cries of the Seasons' by Luke Clennell, published in 1812, are excellent examples. The two drawings, with the cries "Cats Meat, Dogs Meat – Any Cat's or Dog's Meat Today?” and "All Round & Sound, Full Weight, Threepence a Pound, my Ripe Kentish Cherries” are taken from "Cries of London” by The Gentle Author. We know that Richard died a wealthy man leaving in his will properties in Central London, Rotherhithe, Ampney Crucis, Ampney Peter, Stow and Easington. History often throws up some strange coincidences such as this one: in 1802, the partnership between two London scalemakers Charles DeGrave and John Sawgood was dissolved by mutual consent. Richard Wood together with two suppliers to the trade took over the debts of the business. DeGrave later came back into the scalemaking trade, and was one of the firms that became part of another scale business – Avery. Richard and Ann’s two children died young, so the business was inherited by his nephew Robert (1790-1859). There is a brief mention of Robert in a court hearing in the 1830s – he was a witness to a robbery in Smithfield Market. After his death in 1859, the Wood business was shared by his two sons, Robert Henry (1817-1897) and Henry (1818-1881). Like many a sibling partnership, the business ended in acrimony within two years; Robert Henry went off to run the business in Maidstone. Henry stayed to look after the Smithfield side but it soon ran into financial difficulties and in 1867, the sheriffs were called in. At this point the Herbert family stepped in to take over the Woods scalemaking business. They must have spotted a good business opportunity because we are still flourishing after 143 years. Memories of George Herbert  We know a lot about the history of Herberts in the 19th century through our archives, personal researches and the invaluable testimony written by the 81-year-old George Herbert in 1923. George was the son of the founder Thomas Herbert (1811-1876) and Sarah Brinkhurst (1809-1901). The family came from London’s East End and that is where the Herbert business first flourished. George tells us that Thomas was originally employed as an errand boy in Pallett's scale makers business in Leadenhall Street. We know a lot about the history of Herberts in the 19th century through our archives, personal researches and the invaluable testimony written by the 81-year-old George Herbert in 1923. George was the son of the founder Thomas Herbert (1811-1876) and Sarah Brinkhurst (1809-1901). The family came from London’s East End and that is where the Herbert business first flourished. George tells us that Thomas was originally employed as an errand boy in Pallett's scale makers business in Leadenhall Street.Thomas Pallet had died in 1813, and the business was then run by his widow Elizabeth and her sons. Thomas dearly wanted to be a scale maker, but for some reason the Pallett’s refused to let him become an apprentice. After Elizabeth’s death the firm went downhill, so Thomas saw a good business opportunity and left around 1842 to set up his own business working from a shed in his father-in-law Benjamin Brinkhurst’s back garden. His first customer was a butcher and as his reputation grew, so did the one-man business. Moving out of the shed, Thomas obtained a shop in Cannon Street, St George in the East, and took on two of Pallett’s former employees. Thomas Herbert’s business did very well producing small scales used to check the accuracy of gold coins which were commonly being clipped by fraudsters. Those early scales sold for one and two guineas a pair, and also due to the ‘Gold Hurry’, ‘people were mad to buy them’. The business was still very much a family affair; George recalls that his mother Sarah would put the baby to bed and then go and help her husband string the scales. In 1849 the growing business moved to St George Street and in 1857 bought the business of George Birch, scale maker of Grays Inn Road, King's Cross. George’s elder brother Thomas Benjamin took over this side of the business but as the trade flourished, relations between father and son grew acrimonious. In 1863 Thomas Benjamin suddenly left the firm and his wife of two weeks, booked a ticket to America under an assumed name, and signed up to fight in the American Civil War. He contracted TB in that war and eventually died in a military hospital in 1887. As a result of Thomas Benjamin’s disappearance, the Herbert family moved into the rooms above the King’s Cross premises and George became destined to enter the scale makers’ trade. Up to that point he had worked variously for a lace machine manufacturer, an oil and colourman, and in an architects office. In December 1863, George now 21 was brought in as a partner in his father’s business – celebrated by a dinner at the King’s Head in Chigwell – and his brother William joined a few years later. George tells us that he worked at the St George Street premises and had to walk for an  hour each way to get to work. Things got easier when the Metropolitan Underground Railway opened from Farringdon Street (later Moorgate) to Paddington. The staff at the St George Street business consisted of four or five men, an apprentice, an errand boy and a pony cart. George recalls that they forged and filed counter weighing machines and larger pieces of equipment on site. They used an outdoor forge to produce inverted and large beam scales, then filed and finished them indoors. George’s initial task was to do the painting, japanning and writing the names on scales. In the 1860s business flourished, especially due to the nearby London Docks where goods came in from around the empire. We were particularly busy weighing sacks of sugar.  Apart from scales, the business also involved supplying and fitting piping for gas installations and in one case, speaking tubes for a London hospital (this was a precursor of the telephone). Apart from scales, the business also involved supplying and fitting piping for gas installations and in one case, speaking tubes for a London hospital (this was a precursor of the telephone).The company also incorporated spring balances and made steelyards to weigh the coal being unloaded at various ports. It was common for coal porters to try and steal coal for their own uses so accurate measurements were essential. On the move to Smithfield ...  A flourishing business in equipment servicing continued – one of the new customers being a certain J Sainsbury in 1869. In around 1875, George and his family went to live above the premises in 6 West Smithfield and also leased next door. Thus was born the Herbert main offices at 6&7 West Smithfield. By this time Thomas Herbert had retired from the business, and left the management to his two sons, George and William. But only 9 days before their father died in 1876, the sons dissolved their partnership. George took on the mantle of running the Smithfield and St George Street businesses; his brother William Alfred took over the King’s Cross premises. George's side of the business grew both internally and with the canny purchases of other firms such as Medhurst Scales and Platform Machine makers and W Hislop, an Edinburgh maker of very special ‘cheese tasters’ which proved to be a good seller. He completely rebuilt 6&7 West Smithfield in 1889 and on the occasion of the opening of the new premises held another dinner at the King’s Head in Chigwell, commemorated with a tankard engraved with the names of those attending. (The building is now a wine bar but you can still see the lion emblem there minus the scales in its paw.) George also holidayed in France where he saw some good value French scales in the shops there. He instantly took a horsedrawn taxi across to the manufacturer, signed a distribution agreement and for many years did a roaring trade in these balances. The two brothers traded amicably for a time but George’s relative success caused tensions. ... and into the 20th Century  The growth of the family business took a major turn in 1909 when the firm became a limited company: Herbert & Sons Ltd. George’s move led to a major rift with William who tried to register his business as Herbert & Sons Scalemakers Ltd, but after legal action was forced to change to Herbert & Sons (Kings Cross) Ltd. The two arms of the business did not come together until 1948 – 72 years after the initial split! It was around 1910 that the company launched its Lion Quick Action Scale. This proved to be a best seller: it was the lynchpin of the company’s success right up to World War II. George had three sons: George Jnr, Fitz and Arthur.George Jnr joined the business around 1890, Fitz in 1900. Like many a father and son, George Snr and George Jnr had a row and the son promptly quit the business. Fitz took over the company completely about the start of World War I and the photograph taken in 1915 shows him with a staff of 43. The company was also now engaged in war work, mainly shell weighing and equipment for army cookhouses. The growth of the family business took a major turn in 1909 when the firm became a limited company: Herbert & Sons Ltd. George’s move led to a major rift with William who tried to register his business as Herbert & Sons Scalemakers Ltd, but after legal action was forced to change to Herbert & Sons (Kings Cross) Ltd. The two arms of the business did not come together until 1948 – 72 years after the initial split! It was around 1910 that the company launched its Lion Quick Action Scale. This proved to be a best seller: it was the lynchpin of the company’s success right up to World War II. George had three sons: George Jnr, Fitz and Arthur.George Jnr joined the business around 1890, Fitz in 1900. Like many a father and son, George Snr and George Jnr had a row and the son promptly quit the business. Fitz took over the company completely about the start of World War I and the photograph taken in 1915 shows him with a staff of 43. The company was also now engaged in war work, mainly shell weighing and equipment for army cookhouses.After spending several years working in Australia and elsewhere overseas, youngest brother Arthur came home in 1933 to join Fitz in the business. Another important newcomer to Herbert & Sons Ltd was Leon Bagrit who joined the firm in 1929. He left in 1934 and formed the rival Swift Scale Company. Sir Leon subsequently became chairman of Elliott Brothers, one of the UK’s first computer manufacturers, and gave a 1964 BBC Reith Lecture. In 1937, the company built new works on the North Circular Road at Edmonton. Between 1939 and 1945, the company moved almost entirely on to war work, producing many components for aircraft. After World War II, succession was a problem: Fitz’s second son had been killed in a Mosquito over Holland in October 1944 whilst on a photo reconnaissance mission. He received a posthumous DFC. Arthur’s eldest son Jack had been captured in Singapore in 1942 and spent the remaining war years in a Japanese prison camp working on the Burma railway. Post War: The digital and supermarket age  1968: The company’s new home at 18 Rookwood Way, Haverhill The Immediate post war period saw the arrival of Jim Herbert. Jim had not expected to be in the business having planned for a career as an architect. His father and uncle though managed to persuade him otherwise and after being demobbed from the army, he joined the company in 1946. In 1948, the King’s Cross business was in poor shape and it was taken over, bringing the two sides of the family together again. But by then, Fitz and Arthur were in  outright conflict, only resolved in 1952 when the company chairman, Sir Edgar Sylvester, managed to persuade the warring brothers to retire on the same day. Jim took control and seven years later in 1959 the company built new offices within the Edmonton factory and closed its Goswell Road and Charterhouse Street sites. The following year the iconic 6&7 West Smithfield office was closed. outright conflict, only resolved in 1952 when the company chairman, Sir Edgar Sylvester, managed to persuade the warring brothers to retire on the same day. Jim took control and seven years later in 1959 the company built new offices within the Edmonton factory and closed its Goswell Road and Charterhouse Street sites. The following year the iconic 6&7 West Smithfield office was closed. Another important event happened that same year that was to change the fortunes of the company. Herbert & Sons bought the Swift Scale Company and with it came a rather important new customer: Tesco Stores. How have Herberts continued to flourish for so long? Part of the answer lies in its flexible and positive attitudes to change and its ability to lead the field. The 1960s to 1980s are a case in point. Over this period the company pioneered and consolidated the application of electronics to retail weighing machines in the UK. Development commenced in the mid 1960s at Angel Road, Edmonton and the UK’s first retail digital scale was approved by the Board of Trade in July 1968 under National Weights and Measures pattern 1488. That same month the company moved its main operations out of London and set up its new home in the expanding town of Haverhill. But problems with the electronics supplier meant that the groundbreaking digital scales were not launched until 1971 – that delay nearly cost the company its existence. Following the abolition of pounds shillings and pence in February 1971, Herberts launched the ‘Lion Monarch’ which was able to calculate prices in decimal currency. In April 1972 the Council of Industrial Design included the Monarch in its Design Index. This was a true acknowledgement of the quality of design in the new scales. A steady increase in sales over the next three years included installations in prestige customers such as Harrods and volume orders from Tesco’s. Machines were successfully exported to New Zealand and South Africa.  In 1974 work began on a successor to the Monarch. The Lion 2000 was a hybrid design and the initial version of the machine was approved in June 1975. The machine incorporated many improvements and innovations such as a price-entry keyboard, rapid settling time and speedy weighing resulting in the display of computed price within a second. It was possible to totalise and display the sum of the prices of up to 99 weighed items. In 1974 work began on a successor to the Monarch. The Lion 2000 was a hybrid design and the initial version of the machine was approved in June 1975. The machine incorporated many improvements and innovations such as a price-entry keyboard, rapid settling time and speedy weighing resulting in the display of computed price within a second. It was possible to totalise and display the sum of the prices of up to 99 weighed items. The electronics were particularly innovative, representing a very early application of microprocessors – the result of collaboration between Gould Advance and General Instrument Microelectronics. But the development cost put a huge strain on the company finances, which the clearing bank refused to cover. However once funds were secured from a merchant bank, E.S. Schwab & Co., the Lion 2000 proved to be particularly successful product with buoyant sales throughout the late 1970s. As a consequence Herbert & Sons were able to secure a substantial share of the UK market for electronic retail weighing machines. In October 1977 a joint venture company, Lion Electronics Ltd, was formed by Herbert & Sons and Gresham Lion. Production began in the autumn, Lion Electronics being located in a partitioned off section of the main production area at Rookwood Way. In order to provide a clean environment for electronic assembly the area was covered with a canvas roof and became affectionately known as the ‘tent’. In March 1979 Herbert & Sons acquired the Gresham Lion holding. The sales success of the Lion 2000 series coincided with a surge in demand for fast and  reliable label printing. Supermarkets and other multiples were rapidly automating many store activities and this extended to electronic check-out systems. The need to clearly label goods rapidly was becoming essential. In 1979 Herbert & Sons collaborated with Swedish supplier Swedot AB of Gothenberg to link their market leading dot matrix label printers to weighing machines. The Lion 2000/Swedot printer combination provided a speedy cost effective labelling system that was particularly attractive to supermarkets. From this point in time Herbert’s would be known as weigh label specialists. reliable label printing. Supermarkets and other multiples were rapidly automating many store activities and this extended to electronic check-out systems. The need to clearly label goods rapidly was becoming essential. In 1979 Herbert & Sons collaborated with Swedish supplier Swedot AB of Gothenberg to link their market leading dot matrix label printers to weighing machines. The Lion 2000/Swedot printer combination provided a speedy cost effective labelling system that was particularly attractive to supermarkets. From this point in time Herbert’s would be known as weigh label specialists. Also by 1979 Herbert & Sons had begun researching a successor to the Lion 2000 series. By now load cell technology had matured – one could weigh twice the capacity of a Lion 2000. So the company decided to move to load cell technology and developed the ‘Lion Sovereign.’ 1980's and beyond ... In 1982 the labelling capability of the Sovereign range was enhanced by linking to printers incorporating thermal printing technology. By now pre-printed bar codes were in general use on food packages to enable the description of items to be ‘swiped’ and read at check-outs and a range of products for the food industry was developed.’ Thermal printing technology enabled the reliable and speedy printing of bar codes on variable weight items so that they too could be automatically identified at check-out. Printers were linked to Lion Sovereigns with fibre optic cables to assure speedy communication with a high resilience to electrical interference. Although now common place, use of fibre optics at the time was a significant innovation. By the 1980s customers started to demand a fully integrated scale and barcode printer with programmable preset price keys. This was a big challenge for Herbert & Sons who rose to the occasion by seeking out a firstclass partner in Japan.  The result was a collaboration with Teraoka Seiko Co Ltd, better known as Digi. A commercial agreement between the two companies was signed in November 1982 and of course, we are still close partners almost 30 years on. The result was a collaboration with Teraoka Seiko Co Ltd, better known as Digi. A commercial agreement between the two companies was signed in November 1982 and of course, we are still close partners almost 30 years on. The combination of collaboration with world class specialist suppliers and in-house expertise would ensure Herbert & Sons' position as a UK market leader for electronic weigh labelling systems well into the 21st century. This is a brief summary of how the Herbert business developed from its beginnings in 1760 but on these pages we have not attempted to cover any of the events of the last 25 years. |